johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Offering plays, video, acting classes, scholarly critical books, and audio plays, the potential to use Drama Online in the classroom is wide-ranging, from English Shakespeare classes, to drama practitioner classes, and beyond. Keep reading to learn a few of the ways lecturers are using Drama Online to improve the classroom experience for their students, and how Drama Online has transformed teaching by opening up new themes, topics, and ways of approaching the material.

At the Institute of English Studies at the University of Hamburg, drama is an essential part of the curriculum. Students often engage with at least one play in their introductory seminars and, at a higher level, there are entire drama-based courses that look at different aspects or developments in theatre. This way, students encounter a plethora of different plays to explore, whether those are medieval mystery plays, contemporary climate-change productions, or adaptations of Renaissance drama, in which they can analyse representations of gender, class, religion, or even ecocriticism.

However, drama, like poetry is a genre that students often find daunting at first, whether it is the language they find difficult to understand or because they struggle to visualise the play when only reading it. In order to help engage students, lecturers try to arrange visits to local theatres, but of course, due to logistical and financial reasons, seeing an actual performance is not always an option. This is why recorded performances have become a staple in the classroom. The large selection on Drama Online offers both students and lecturers the opportunity to view several different performances (or excerpts) of a single play in order to discuss it further in class. Drawing on my own experience, seeing a play performed not only engages students more, but it also aids their understanding of the play. By also taking into account the characters’ facial expressions, body language, costumes, and the stage set, they are able to grasp contexts much more quickly and pick up on nuances they would otherwise have missed.

Being a tutor for introductory seminars, it has often been my experience that students are initially prejudiced against drama due to plays they had previously encountered in school but later gain an interest once they have worked with a performance. In the tutorials, we discuss certain casting choices, analyse dialogues and the development of the characters and plot, or the use of different theatre codes. By being able to look at one specific scene multiple times and have a different task to focus on each time, the students are able to gain a much more thorough understanding than if we had only focused on the text itself.

One of the lecturers chose Shakespeare’s Othello as the set drama for his seminars and regularly included clips of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2015 production, especially of the ‘temptation scene’ in Act III, Scene 3 to let students experience Iago’s powers of persuasion for themselves. In the tutorials, we then took a closer look at the dialogue and how the power dynamics between Othello and Iago shift over the course of a single conversation.

Another lecturer decided on The Taming of the Shrew for her course and after preparing it, I checked Drama Online to see which productions of the play were available. I decided on showing a few minutes from Act II, Scene 1 from two different productions, the 2013 Globe on Screen version and the 2019 Royal Shakespeare Company one. While the former followed a rather traditional line, the latter swapped the characters’ gender to investigate issues of power in a now matriarchal society. While students were initially shocked by the second excerpt since their expectations were suddenly subverted, this also gave them the chance to think more about the impact the production had on its audience, thus moving beyond the play text itself.

At the beginning of term, I always share a list of recommendations of databases which are particularly helpful to students who are just starting out with their studies. Drama Online has been part of that list, especially since 2020, as it helps make drama more accessible and enjoyable for students. I encourage them to explore different plays on their own and since there is such a large collection to choose from, most students will always find a play they enjoy or even one that relates to their other courses. Having encountered Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and discussed The Wife of Bath’s Tale in one of my own seminars on medieval literature and theatre, I was delighted to find Zadie Smith’s The Wife of Willesden , a recent adaptation, available online. Digital resources like Drama Online have become an integral part of university life and make drama more accessible by not only providing high-quality recordings, but even subtitles and transcripts which are incredibly helpful especially for a non-native audience. We also have access to entire play texts with extensive footnotes that students would have needed to purchase as physical copies otherwise, thereby lessening financial strain and conveniently allowing students access to the texts wherever they are. Overall, these digital resources allow for more varied lessons on drama and easier access to performances that students otherwise would not be able to see, as well as helping to inspire more passion for drama.

For the Case Study focus group I chose the two core second year courses that I teach in the autumn term, Shakespeare Page to Stage and Shakespeare Page to Screen. When I was asked to conduct a focus group with my students, I was keen to include both those studying English and Drama and those studying English and Film Studies. In the past five years things have been changing quickly in higher education. The increased tuition fees mean that students often have little time or money to spare chasing up and buying traditional paper-based resources in the library or the bookshop. Increasingly, at Royal Holloway the students are commuting and working one or more jobs alongside their studies so resources for their courses need to be easy to access and as inexpensive as possible. As a result, I have been increasingly relying on the digital resources we have access to as an institution to create reading lists that are fully accessible online.

While Shakespeare Page to Stage is an established course which forms part of a longstanding programme at Royal Holloway, Shakespeare Page to Screen was a new course this year and one that entirely depends on the new resources available through Drama Online. The course covers four film and television adaptations of each of two plays, Henry V and Richard III, something that would not have been possible before the broadcast and online distribution of the BBC’s series of films The Hollow Crown (BBC, 2012 and 2016). The availability of these resources this year gave me the opportunity to develop a coherent structure, as well as high-quality materials, to teach both the textual and film elements of the course, tracing the development of British film and television history while also introducing the students to theories of adaptation. The fact that the texts and films can be found in one place has made thinking about other courses which trace performance and textual trends possible.

A number of the students admitted that they went to the performances before reading the text or even during their reading of the text in order to deal with either dyslexia or dyspraxia, or both. The students seemed to find the audio recordings particularly useful as a means of helping them navigate the difficult text on paper.

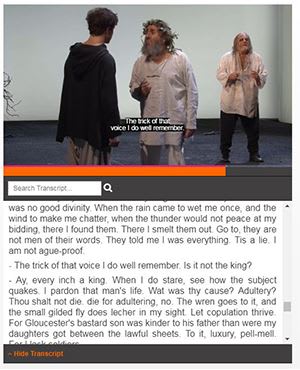

In advance of the focus group I made a point of showing the students the transcription function on the video performance of the plays. It turned out that several of them had already discovered this option and had used it as a means of planning their essays. While others were delighted to discover such an option existed it was not something that they could see the benefits of straight away. However, after some demonstration and discussion, it began to seem that this was now going to provide a key starting point for essay plans in the class. Therefore not only the complex ideas about textuality, but also the issues and practices of creating concordances were made possible to discuss with students at the undergraduate level through demonstrations in class that I was able to do using Drama Online.

The result of the focus group, then, was the discovery that students may begin with much less ability to read and interpret the texts of the plays than they once may have had coming into university; however, through ingenious and studious use of the resources available to them they were able to move through from understanding the texts to exploring quite complex and difficult theoretical ideas about how to interact with these materials. By making ideas about textuality and the usefulness of concordances demonstrable in the classroom it was possible to get the students engaged in what might formerly have been considered quite rarefied research areas.

In the past the curriculums that we put together were very dependent upon the availability of suitable anthologies at affordable prices. In a typical Drama module, students will do somewhere between 6 and 10 plays. That module will be one of 12 classes that they might take in the course of an academic year. If I set too many individual playtexts for them to buy, then my one module is going to blow most of their book budget for the year, even though it only represents a fraction of their work for the year. For that reason, good anthologies have been essential.

The transformative impact of Drama Online has been that all of those issues to do with economies of scale and sales figures have largely vanished. I have much more flexibility to devise thematically-based courses that include both canonical and non-canonical writers, giving students the chance to encounter plays that they would otherwise never have read.

A difficulty with using anthologies is that we often get into a vicious circle. Publishers will be reluctant to publish something unless they know it will be taught, but teachers will only set a text for a course if we know it is in print. The result of this arrangement has been that many of the core drama anthologies essentially reinforced the canon over and again, despite the best efforts of their editors. The overall impact was that the students I was teaching in 2005 were still being taught plays that I had been lectured on myself as an undergraduate in the mid-1990s, even though the field has changed hugely.

This had other knock-on effects, gender balance being one very prominent one. In the area of Irish theatre, it has often been very difficult to find a gender-balanced anthology of plays. Most Irish play anthologies have no more than one play by a female dramatist; several had none. Other problems arose. Because many Irish play anthologies are geared towards an international market, there has been a tendency to publish Irish plays that have been successful in London and New York (because those successes could be used as evidence of future sales). All of those plays were very good but they also tended to be dramas that were not so focused on matters of exclusively Irish importance. In my previous classes on Irish theatre, I often found it difficult to find an affordable anthology that had a good variety of plays by men and women, or plays that would otherwise strike most of the students as directly relevant to their own lives. For a long time, students’ sense of “Irish drama” was being both shaped and distorted by what we were able to teach. This is not to criticize those anthologies: many of them were excellent, and I continue to use them in my teaching. But we now have many more options.

The other major benefit is that Drama Online allows me as a teacher to escape from the (occasional) straightjacket of nation-focused teaching. In the past I’ve often wanted to teach classes that cut across several national traditions—maybe about globalization or the environment or terrorism, for example. And there often haven’t been anthologies available to allow that to happen. But in the last year I was able to do a large lecture course for second year undergraduate English students that was about globalization, economics, and feminism, and which included plays by Lucy Prebble, Lucy Kirkwood, and Caryl Churchill, but which also drew on other national traditions. Again I could not have done that before now, so having access to Drama Online has opened up exciting options for my teaching.

Within our undergraduate drama degree Drama Online has been transformative in allowing us to curate classes that can be similarly wide-ranging and more reflective of theatre as it is seen and made now. Not to generalise but I think most people who go to the theatre see plays by people of many nationalities. Many theatre professionals, especially the most successful, can expect to work in several countries. And the playwrights I meet and talk to are reading Anne Washburne one day, Ella Hickson the next, and Shakespeare the day after. One of the key benefits of Drama Online is that it gives us the world of Anglophone drama as it’s being seen, made, and read now. Our classes can now be more fully aligned with the world that students are watching theatre in and in which they will soon be working.

Last year I was teaching a class on theatre and translation. Because of Drama Online I was able to ask students to compare different versions of Oedipus and Ghosts that are available on the platform. I could not have done that easily in the past. This has been transformative for students because it helped them to see that “translations” are often really versions, and that they themselves can feel free to adapt classic plays in their own way.

I know that as a student recruitment tool, our having Drama Online has been seen as appealing to students, especially at postgraduate level. Probably from a sales point of view someone could do a cost/benefit analysis that would show a subscription to Drama Online having a knock-on impact in student satisfaction and/or enrolment. I see anecdotal evidence of this all the time.